By Eleanor Poulter

While sifting through Natal Witness newscuttings recently, I found myself experiencing nostalgia about Pietermaritzburg. Why should this be?

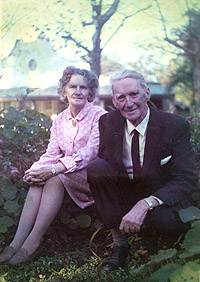

My maternal great-grandmother (Laurie’s meternal great-grandmother), after arriving from Yorkshire in 1861 with her first husband, lived in Pietermaritzburg for a while before they moved to Johannesburg. She returned as a widow with young children, married my great-grandfather, one Robert Benjamin Moorby – mentioned in Alan Hattersley’s books – and had several more children, with my maternal grandmother being born there in 1879. So the ties go back a long way.

Secondly, I have many fond childhood memories of Pietermaritzburg, highlights in my lonely life as an only child living with a middle-aged mother and somewhat crusty step-grandfather in Durban. Being a daydreaming introvert (I think I was Attention Deficit, before it became fashionable!) from a broken home – something of a rarity then – I had few friends.

Although I generally amused myself well enough, the oases of my life were the holidays I spent at my aunt and uncle’s farm in Town Bush Valley. Once I was old enough, my mother would see me onto the Pullman bus in Berea Road. The trip was quite an expedition via the old main road, involving a stop at Drummond for tea.

My aunt would fetch me in ‘Maritzburg and take me to the farm. Glenaholm was my paradise. The cinder driveway, shielded from the road by soughing casurina trees and flanked by beds of agapanthus and hydrangeas, forked to form a loop around the central lawns and the Dutch-gable style farmhouse with its verandah on three sides.

Aunt Phyl had established a beautiful garden. One crossed the driveway from the front steps to a lush lawn edged with a colourful flowerbed. Beyond, orange orchards extended as far as the stream in the valley. On the lawn were pale turquoise swing seats, wire mesh chairs and tables where tea would be served, or – my favourite – sweetened, diluted orange-juice made from the farm’s Valencia oranges.

On one occasion, while very young, I enthusiastically “helped” with turning soil in the flowerbed, using a long-handled mini-fork, and succeeded in putting one of the tines through the skin between my toes. I was whisked off to hospital (about which I remember nothing!) to get an anti-tetanus shot.

One entered the front door past an outer screen door, a vain attempt to keep the perpetual flies at bay, and stepped into the entrance hall that seemed so cool after the warmth outside. To the left were my aunt and uncle’s bedroom suites; while to the right was the large lounge with its fireplace, the windows forming alcoves in the thick walls. Window seats ran under the wide bay-window overlooking the central lawns and fishpond. A wide arch linked the lounge to the billiard room, with its (out-of-bounds for me) three quarter size billiard table. Covers were put on when the table was used for Christmas and other large family meals. Along the inner wall was an imposing cabinet, with glasses behind leaded-light doors in the upper half, and drinks in the lower half.

My early memories of these two rooms revolve around Christmas, when we would drive up for the day. Christmas dinner was eaten at the billiard table (younger children were relegated to a kiddies’ table alongside) and gifts, stowed under the big Christmas tree in the lounge, were handed out by a relative disguised as Father Christmas.

But first the farm-workers, dressed in Zulu tribal dress, would come up from the workers’ compound and gather on the front lawn where they sang and performed Zulu dances, including high-kicks followed by tumbles to the ground, all accompanied by whistles and ululations. This was always an exciting highlight for me. Afterwards, my uncle would hand out “Christmas boxes”, trinkets, beads, bangles, mirrors, combs, shaving kits, etc. I had no understanding of social situation then, and simply revelled in the novel experience.

When I spent holidays at the farm, my aunt would have evening sing-alongs around the piano situated in the further section of the lounge. I loved these parlour songs, especially “The Road to Mandalay” and other “golden oldies”. I had little sense of pitch, so my enthusiastic efforts at singing must have been torture for my musical relatives, but they graciously never discouraged me!

The entrance hall led into an unusual central room with a raised sky-light section. This was the everyday dining-room. To the left, as one entered from the hall, was a passage leading to the toilet and bathroom, appendages backing on to my aunt’s en-suite bedroom. Her room was like an inner sanctum, darkened with heavy curtains when she retreated to endure one of her migraines, while my uncle often played solitaire bridge in his adjoining den.

Angled off the further left corner of the dining-room was an alcove to three bedrooms, one where I slept and two for my twin cousins (the vivacious Laurie and her brother, Ray), seven years older than I and the youngest of my aunt’s five children. Off the far-right corner of the dining room, next to the billiard-room’s inner door, was the door to the kitchen and pantry, a hive of activity around mealtimes, with at least two or three servants, including a cook. Mealtimes, including breakfast, were wonderful feasts. Lunches, when the office-staff could join the family, had two main dishes, one a chicken dish and another non-chicken dish for those who were heartily sick of chicken! Once, when I was at the farm for the Christmas holidays, I was drawn into helping my aunt and Laurie prepare the feast for the family. Since my mother never baked, I was fascinated, watching them decorating a Christmas fruit-cake with marzipan, royal icing and Christmas trimmings.

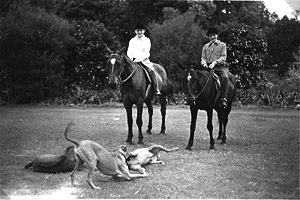

Aunt Phyl bred Rhodesian Ridgebacks, so there were always several dogs around – I mostly remember timid Claire, big Julius, and much later, bouncy Roux. The perennial litters of puppies were kept in the stables and later in enclosed “runs” until they went to their new homes. No cat was safe on the property except (remarkably) the series of white laundry cats that stayed in the old-fashioned laundry with its concrete sinks, scrubbing boards, hand-operated mangle and damp scent of sudsy water and open drains. After I once trimmed the cat’s whiskers in a moment of childish idleness, one of my older cousins came after me with a knife. He was teasing, but I was terrified!

My wanderings included the rooms where the eggs were packed, and I was intrigued by the rooms of incubators for hatching eggs. The chicken-sexer who skilfully examined and separated the baby chicks fascinated me, although it seemed heartless when he broke a reject’s neck.

One of my favourite activities was riding the solid-tyred bicycle that was kept for me on the farm and which my cousins taught me to ride. I would bump down the dirt road past the free-range chicken houses and the barn where the harvested oranges were stored, as far as the fence with the stile, beyond which was the area where chickens were slaughtered the old-fashioned way, with an axe and a chopping block. Nearby were the pigsties, with the pigs grunting and squealing whenever anyone came near them. My cousins and I used to collect acorns in Alexandra Park when my aunt took the dogs for a run there, and we’d feed the acorns to the pigs. I got into serious trouble with my cousins when in a mischievous moment I tossed some stones into the pigsty. My cousins guessed I was the culprit, even though, in my terror at being accused, I denied it.

My usual cycling route, however, was to turn left just before the barn and speed down the dirt path that led past the stables, then along the paths through the orange orchards, jolting through the irrigation gullies. When I got older, I occasionally rode down as far as the “native compound”, a collection of dormatries and huts. Coming from the city, speaking only English and a smattering of “Fanagalo”, I couldn’t really communicate and so would just smile and greet the women and children, before racing back through the orchards. I normally only went down there with my cousins, to catch the horses grazing on the hill across the stream, and my cousins would greet the workers and talk to them in fluent Zulu.

Set well away from the farm-house in the middle of the orchards was a large reeking rubbish pit area, a major source of flies, so I only went along there to the stream with my cousins. Otherwise, I used the path near the farm entrance, running alongside the water pipe from the pump at the stream. An old pre-refrigeration “meat safe”, situated alongside the path, always intrigued me. Nearer to the gate, my cousins in their younger years had hammered six-inch nails into the gum trees, and I remember once we climbed up to a seemingly dizzying height – a thought that now petrifies me!

The main highlight of my stays at Glenaholm was horse-riding with Laurie and Ray. They taught me how to ride on a sedate Basotho pony, imaginatively named Blackie. Once I’d learned the basics, we went on out-rides through the plantations across Town Bush Road, Laurie riding her grey, Foam, and Ray on his chestnut horse, Siani. Like many little girls, I fell in love with horses and became besotted with them. We would ride along the plantation roads, the horses’ unshod hooves clopping along softly, sometimes on a layer of pine-needles.

There was the thrill of being able to canter as I became more experienced, and I was proud of my ability to rise correctly when the horses trotted. Unfortunately, that is as far as my riding skills progressed, since by the time I reached high school, my cousins were pursuing their tertiary education. A tennis court had been built by then, and I spent many hours using the practice wall.

After my mother fell out with her sister, my holidays at Glenaholm ceased until the end of my Matric year, when I spent five weeks with my aunt at her invitation. In the interim, I spent a couple of holidays on the other family farm near Bishopstowe, where the daughter of my cousin Cuan stayed with her mother and siblings after their return from farming in England. The horses were moved there, so Pippa and I could explore the area on horseback.

It is true that one can never recapture one’s memories. My uncle passed away and then, as my aunt got on in years, the farm had to be sold. I desperately hoped that someone would buy it and preserve the house, but it was not to be. After it had been vacated, my husband and I went to see the farm during a rare trip to Pietermaritzburg to see a friend down from Johannesburg. The garden and orchards were overgrown, the house empty, the farm buildings deserted and semi-derelict. With aching sadness we left, not to return until 2003 with our teenage sons, after we had visited relatives in Town Bush Road.

We turned into a road near the former Glenaholm entrance and encountered a desolate scene. A soulless, flat area on the left culminated in a shopping centre. The valley with its surrounding hills looked smaller than I remembered, even though I’d seen the farm after I left school. I recognised the hill across the stream, where we used catch the horses. It also seemed smaller. Does one’s memory make things larger than life? At least the hill was still there, but otherwise – an urban wasteland.

My husband, like most males, is not one to stop and look, and in a few seconds we were in a built-up suburb, heading back to the N3. My heart was heavy over the lost beauty of a place that lives on only in my memory and the memories of those who knew and loved Glenaholm.